Originally published in the Noircon 2012 Proceedings

Edited and Produced by Lou Boxer, Deen Kogan, and Jeff Wong

November 2012

Philadelphia, PA

Introduction

It might be a bit surprising to note that the legacy of TV noir stretches back almost seven decades. That is nearly as long a history as its more celebrated competitor and inspiration, film noir. While the first films noir were shot between 1941-1945, as Ray Starman notes in his book TV Noir, the first noir TV series made their debuts in 1949 with Martin Kane, PI and Man Against Crime. Of course, there is a major and indisputable reason why TV noir came after film noir. While Hollywood was reaching the apex of its studio era in the 1940s, there were really no TV networks until 1947.

But since 1949, noir has been a constant staple of television programming, generating hundreds of series and thousands of hours of viewing pleasure. Given its plentiful output, cultural impact, and historical legacy, it is likely that more people have encountered noir stories watching TV shows in their living rooms than by sitting in movie theaters. Yet in terms of scholarly and fan-based activities, there have been more books and festivals dedicated to film noir than TV noir. TV noir is often dismissed as “inferior” to film noir, and many fans of noir will tell you they don’t “watch television.”

These are my working notes to accompany the 2012 Noircon panel, “Crime in Primetime: TV’s Most Innovative Noir Series.” Both here and during the panel, I will make a case for reassessing TV’s contributions and innovations to the noir style and storytelling. Towards these ends, I will briefly lay out some of the major ways in which TV noir differs from its cinematic counterpart in terms of its forms, authors, and constraints, and some of the reasons why you should be watching some truly exceptional television series right now if you are a fan of noir.

1. The Forms

Noir and film noir appear on television in a myriad of ways from the replaying of classic movies to throwback skits on variety shows to “special episodes” of non-noir TV series. In this last instance, the noir style is mostly an excuse to shoot an episode in black and white, smoke cigarettes, and wear fedoras. In fact, the grisly crime stories that open many local nightly news broadcasts might be the most noir productions on TV. The pre-eminent form of TV noir is the one-hour prime-time drama. The one-hour drama is not actually a full hour. If you take into account the commercial interruptions and the station identifications, most hour-long shows are approximately 42 minutes long. Each episode of a noir TV series is considerably shorter than the typical length of a classical film noir, which typically run between 90 and 120 minutes.

Another major difference from the movies is TV noir’s serial format. TV noir is ultimately about the series—depending on the era and the network that means anywhere between 13 to 26 episodes per season. Therefore while Hollywood movies clearly were an influential source for early TV, the bigger influence in the beginning was commercial radio. Television appropriated one of radio’s main programming strategies: the regular and predictable rhythm of a prime time schedule.

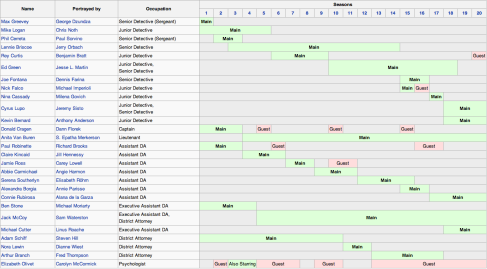

TV noir’s profuse output makes it harder to discuss these series in the same depth with which we can analyze films noir. It’s a matter of scope and scale. Consider Law and Order. Over its twenty year run, the original Law and Order series produced 456 episodes. That is an astounding narrative archive that would take almost two months to view in its entirety if you watched eight episodes a day (as seen in the chart that tracks the major characters over 2o seasons, from Wikipedia, below). Such a large number of episodes also raises the difficulty of being a TV noir completist, i.e. the likelihood that you have seen every episode of a series. And multiply that problem by hundreds of series, and you can see the analytical difficulty of writing about and discussing TV noir.

In terms of serial structure, each episode of a series can be a self-contained story, which can sometimes feel like a slimmed down (or for some, a watered down) version of a film plot with a rushed and frequently predictable resolution. Or shows can employ the concept of continuing storylines or story arcs to extend narrative events over multiple episodes. Story arcs can tell a more complex story that unfolds over dozens of hours of viewing. Some of TV noir’s most innovative shows have opted for this latter approach. Shows like The Wire and Breaking Bad use intricate story structures to achieve an almost novelistic storytelling depth that is simply impossible to attempt in a ninety-minute film noir. Long-running series have their benefits.

Having to generate a new noir story every week also meant that TV noir returned to its serial roots in pulp fiction and mystery magazines. There can be a thrilling vicariousness in watching a well-made TV noir because you establish a powerful connection with characters that can extend and deepen for years. But the ongoing run of a TV series can lead to challenges for writers who have to make sure the show’s major cast members survive the impending doom of the fateful noir universe, robbing many TV noir series of the narrative uncertainty that has certainly animated some of our best films noir.

2. The Authors

Film has always tended to be identified as a director’s medium. First raised by the concept of auteur theory, directors are assumed to be the main creative driver behind a film. It is just not the same on television. An episodic TV show requires a unified look and similar directing style over multiple episodes, so it is important for directors to “stick to the script.” Even if a director wanted to get more visually adventurous, there is not enough time in pre-production to execute such ideas, and it’s the producers (not the director) who hire the creative personnel on the set. Even with such limitations, some well-known directors have been drawn to the small screen including David Lynch (Twin Peaks), Alfred Hitchcock (Alfred Hitchcock Presents), Martin Scorsese (Boardwalk Empire), Quentin Tarantino (episodes of CSI:), and Rian Johnson (an episode of Breaking Bad).

But ultimately, television is a producer’s medium. For example, name a director of a recent TV episode you watched. Did you draw a blank? Don’t feel bad. Most people don’t recall who directs a TV episode, because we conventionally attribute authorship of a TV series to a producer or show creator. Now name a TV producer. Who created Hill Streets Blues? The Streets of San Francisco? Law and Order? Breaking Bad? For most who have watched these shows numerous times, the names Steven Bochco, Quinn Martin, Dick Wolf, and Vince Gilligan would likely come to mind.

But Bochco, Martin, Wolf, and Gilligan (even when they also write entire episodes for their own series) tend to more in control of a team of writers who operate under the constraints of the show’s template. This point returns me to my essay about networked authorship for Noircon 2010, where I examined the role of multiple writers on a film noir script. My argument was that there was much cross-pollination among creative personnel in classical Hollywood and the writing behind many films noir might be best understood as the hybridization of shared interests in hard-boiled stories and creative exchanges rather than the work of single auteur. I used Strangers on a Train, and the roles of Patricia Highsmith, Raymond Chandler, and Alfred Hitchcock as my example.

If we turn our attention to TV writing, the idea of networked authorship is its basic creative model—even more so than film. TV series must employ teams of writers and directors to meet the stringent production demands of producing between 13 and 26 episodes in a short time frame. This means that the show’s creator tends to be the creative hand that guides the overall evolution of the series, but separate writers are credited with individual episodes. Increasingly, some of our best noir TV shows have raised networked authorship to a new level. HBO’s The Wire might be one of the best examples. That show’s creator, David Simon, hired some of the best literary noir writers in the business to pen episodes, including George Pelecanos and Dennis Lehane. As a result, the quality of The Wire’s writing shines in that series. (Image from Time Magazine, by David Johnson, picturing Ed Burns, David Simon, and George Pelecanos in Baltimore, where The Wire is set)

Moreover, like the Hollywood studio system that preceded it, TV noir can build new series on pre-existing literary properties. TV noir over its seven decades has been dominated by topical series that seem to be tireless retreads of “ripped from the headlines” stories, but TV noir can and has benefited from adapting hard-boiled literature. While one of the more prominent examples might be a show like the 1980s’ Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer, consider a couple shows like Justified and Wallander. The first show, a hit on F/X, is based on a character created by Elmore Leonard, and the latter show, a series from the BBC, is based on Swedish novelist Henning Mankell’s internationally known police inspector, Kurt Wallander. While source material alone is no guarantee of quality when adapting for a new medium, Justified‘s writing has clearly benefited from a rule shared among the writing staff: when in doubt, WWLD? (What would Leonard Do?) (Image from NJ.com, Elmore Leonard with Timothy Olyphant of Justified)

3. The Constraints

As we begin to consider the most innovative noir series in TV history, I believe we will find that the constraints of TV have fueled those shows in powerful ways. As Shannon Clute and I discuss in our book, The Maltese Touch of Evil: Film Noir and Potential Criticism (Dartmouth University Press, 2011) there are very good reasons to look at films noir as “constrained texts.” Moreover, some of our most creative noir films have consciously embraced constraints to reveal noir’s potential.

From its earliest days, the TV industry has been subjected to more constraints than the film industry. Part of this is due to the fact that TV was projected directly into our living rooms. Therefore, long after film noir shook off the most restrictive forms of censorship, TV’s versions of noir tales had to meet prime-time viewing standards on broadcast networks and depictions of sex, violence, and use of language were heavily censored well into the 1990s. In 1993 NYPD Blue could still use censorship constraints in its pursuit of quality storytelling. Blue (as the show was frequently referred to) intentionally stirred controversy with partial nudity and adult language that now seems tame compared to pay-cable outlet shows like The Sopranos, as in this clip of NYPD actress Charlotte Ross. But pushing against the constraints of broadcast standards did much to usher in today’s more complex noir series.

TV budgets were also historically lower than for films, so TV shows tended to be restricted to a few sets that got reused in almost every episode. Many TV noir sets can have the feel of a locked room mystery. Location shooting was typically too expensive, so TV began to reuse old movie studio sets in ways reminiscent of Poverty Row studio practices. But this constraint also became one of TV’s biggest contributions to noir. TV noir tended to seek a distinctive “locale” for exterior shots that would give the show a geographic identity and to differentiate series from one another. This moved TV noir stories beyond the urban environs of LA, New York, and San Francisco (though plenty of noir shows are still set in these cities). On television we get more noir than expected from sun-drenched locales such as Hawaii (a favorite destination of crime shows, such as Magnum, PI) or Miami (Miami Vice or CSI: Miami). We also get noir in some of the smaller regions of the US, as in Justified (with its great use of Harlan County, Kentucky) or Breaking Bad (and the emergence of New Mexico as a noir border crossing region)

TV had a much more restricted image size. Compared to the “big screen,” early television sets were extremely small. The quality of the TV image could never compare to a film print (until extremely recently in the digital age, and still a digital print can’t match a well-struck 70mm Technicolor print). It was not even a fair comparison. TV in the 1950s was a blurry, pixelated, and electronically refreshed mess compared to the luxurious richness and dense visual field of projected film. And the technological indignities continued over the decades: TV developed color long after film, new sound technologies were slow to be adopted. Sometimes, with the rise of HDTV, we forget all that.

Visual personnel working on TV series have had much greater limitations in visual design and cinematography. This meant that until fairly recently TV was not focused on visual storytelling as much as narrative design and the growth or goals of recurring characters. A show like The Fugitive in the 1960s is a great example. Dr. Kimble’s four season pursuit of a one-armed man was used as a continuing story arc to find a creative benefit from episodic storytelling. Since TV, like film, constantly recycle narrative strategies, The Mentalist pursues a similar narrative structure with a serial killer named Red John.

Perhaps one of the best TV shows of all time is Breaking Bad (this is the TV series I will discuss on the panel, “Crime in Primetime”). The show’s creator Vince Gilligan is on record as being a fan of constraints, and mentioning that he has embraced constraints in the writing and design of Breaking Bad. Gilligan’s embrace of constraints can be seen in the final product. The show has a fairly small number of cast members for a show going into its fifth and final season. The show has played out over a restrictive time frame, roughly a year of action over the first four seasons. The show elegantly uses the “cold open” (a modern variant of in media res) to introduce visual metaphors and plot elements that engage the viewer into the complex world of Breaking Bad, as in the recurring and ultimately deeply meaningful motif of the pink bear in Season Two.

And the show uses the character of Walt White—a high school teacher turned meth cook—to examine with an uncanny depth and human perspective the global reach of today’s decaying noir universe. And Gilligan does all this under the censorship constraints of AMC, a basic cable station.

Conclusion

What are the most innovative TV noir shows? I’ve only begun to scratch the surface of crime, mystery and noir drama on the small screen. For seven decades, TV has supplied memorable (and some not-so-memorable) noir programming that has advanced noir storytelling. But with shows like The Shield, Justified, and Breaking Bad, TV noir is in a period of renascence. Noir stories are becoming more complex and intricate. New technologies and higher budgets have allowed TV noir to expand its visual design. And long-form stories are becoming ever more elaborate in shows such as 2007’s Forbrydelsen (a brilliant Danish police procedural recently remade by AMC as The Killing–the image below is of the character of Sarah Lund from Forbrydelsen).

Noir’s seventh decade is off to a great start.

Let the debates begin.