“Free their books and their minds will follow.”

–Masthead slogan for The Concord Free Press

1. The Experimental Reader

In yesterday’s post (“As We May Publish”) I discussed what authors might consider taking away from AAUP’s report on “Sustaining Scholarly Publishing.” My reflections were oriented around why authors should care about the changes currently underway at university presses. I also mentioned that my interest in this topic was being driven—to some extent—from my own authorship perspective: my experiments in open access publishing, my interest in alternative scholarly publishing, and my forthcoming university press book that has digital and database logics at the core of its critical methodology.

As a companion set of ideas to that post, I look today at two publishing experiments that came to my attention as a reader of a particular genre of fiction. With a background in English Literature and as a scholar of film noir, I read noir fiction and hard-boiled literature. That genre—coming out of the pulp magazines, the dime novel, and the comic book—has always been at the forefront of publishing shifts. Noir authors and noir publishers have tended to adapt to new business models while retaining (and even extending) their core thematic interests and stories. Through my interest in that genre, two experiments came to my attention that I don’t think are yet widely known in digital humanities circles. I bring them up as case studies that have piqued my interest as a reader who likes to explore publishing experiments—and these examples come out of the “wild” category of the publishing ecosystem—and they help me think about the reader’s role during this moment of experimentation.

My first example will be Concord Free Press, which gives away its books for free–literally. But that is only part of the story: Concord Free Press has a particular institutional mission that asks readers to make voluntary donations to the charity of their choice in exchange for a free book. The Concord Free Press calls its mission “generosity-based publishing.” My second example is Level 26, a new media publishing venture started by CSI: creator Anthony Zuiker. His Level 26 venture involves book publishing, web community and video productions, organized around what Zuiker calls the “digi-novel.”

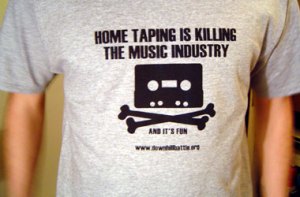

Though my two publishing examples are very different, both share a desire to “free their books” and encourage their readers to “give back” in highly structured ways via the open Web. I am not using the word “free” as in “free beer” (one of my favorite lines from Lawrence Lessig in his book Free Culture) but “free” as in “free speech,” “free culture,” and “freeing” as in “liberating” or “having independence.” To me, these projects are interesting to consider in light of the ongoing conversations around the sustainability of scholarly publishing. These examples strike me as publication models that are taking advantage of digital affordances. They are asking new questions about the role of presses, the nature of the “book,” and the participation of readers in online activities.

2. Scott Phillip’s Rut and the Generous Reader

“If you took the tender portrait of a town in decline in Richard Russo’s Empire Falls, mixed it with Kurt Vonnegut at his most satirical and biting, then sprinkled in a few grams of meth and a generous shot of piss from a syphilitic hobo into the resulting solution, you’d have a drink that could almost put you on your ass as fast as Rut sure-as-shit will.”

Review of Rut by Spinetingler Magazine

Scott Phillip’s most recent book Rut was published by Concord Free Press. Scott Phillips is best known for his novel The Ice Harvest, which was also turned into a neo-noir film starring John Cusack. Instead of going with a traditional publisher, his latest work is being distributed for free by Concord. What this means is that it does not cost anything to obtain a copy of the book. It is actually free (as in costing no money). However, there is a reason for this. Concord Free Press asks all readers who take possession of the “free” novel to make a voluntary donation to the charity of their choice. The book-as-giveaway is used an incentive to increase charitable donations. And so far, the experiment is paying off. Concord Free Press has raised over $200,000 dollars in donations via the books has it published.

Now, it is important to note that its books, including Rut, are not published as e-books or released as PDFs—they are only available as traditional paperback novels. In fact, in one of my favorite parts of this experiment, the back page of each novel has ten blank lines where each reader of the book is supposed to sign their name and then pass the book along to another reader. This decidedly analog approach to forming a network of readers is a great way to encourage an ever-expanding readership. The physical book operates metaphorically a little bit like a digital bit; it is not meant to sit on one’s shelf, but is always intended to be in transit to another reader. It’s a virtuous model of sharing: the reading circle as lending library.

How do online communities come into play here? Concord Free Press hosts a website and asks all of the people who donate due to one of their books to log onto their site (www.concordfreepress.com) and note where they gave and how much. What one notes when visiting Concord’s website is how many donations are significantly more than the reader would pay at a bookstore for a 230 page novel like Rut. It is not uncommon to see donations of $25.00 and higher, suggesting that one act of generosity (giving away a book by an established author) results potentially in a greater act of generosity (a donation in excess of the typical consumer purchase of a paperback).

ForeWord Magazine says that Concord Free Press “re-conceptualizes the very goals of publishing, a grand experiment in subversive altruism.” It is this aspect of the experiment that I want to consider most closely. While Concord’s “subversive altruistic” model will not necessarily work for all publishers and all authors (note that Concord Free Press is publishing the work of already established authors), it is worth considering how models of “generosity” can induce and support participation via the open Web. [As an aside, is this type of generosity akin to the free labors that go into supporting a publication model like Wikipedia?]

At this point, the publication model of the Concord Free Press raises more questions than answers for me. Still I want to explore the implications of this kind of experiment on scholarly publishing. What would the scholarly version of this experiment look like on the open Web? How could scholars benefit from giving away books for free and asking for audience participation in return? Would a model of “book sharing and lending” (which is also at the heart of Concord’s experiment) work for a scholarly book? Is the logical extension of Concord’s paradigm to publish their novels in digitally native formats and remove the need for actual physical book publications? How might scholars locate funding to write books that encourage “subversive altruism?”

3. Anthony Zuiker’s Level 26 and the Active Reader

“Not a hint of this appeared in the mainstream press. This material was relegated to a bunch of serial-killer-fan web sites, the most active being Level26.com.”

–Self-conscious, metatextual reference from the novel, Level 26: Dark Prophecy (p. 117)

CSI: creator Anthony Zuiker is exploring the “digi-novel” in a series of crime stories focused around a criminal profiler, a “Special Circs” agent named Steve Dark. Two novels in the series have already been published, Dark Origins and Dark Prophecy. Each novel is supported by (even architected around) digital components and an online community. There is a website, Level26.com, where fans can meet up. There are videos that function as “cut scenes” interspersed throughout each novel. There are the Level 26 apps that bring the novel and its digital components into one application. A quick disclaimer: I don’t think Level26 is everyone’s cup of tea. The story itself can be quite gruesome (a bit beyond where even the CSI: TV series will go) and will mostly appeal to hardcore fans of Zuiker’s TV shows or mainstream readers of the serial killer/mystery genre.

Zuiker’s vision for the “digi-novel” seems to be a digital convergence between the storyworlds of television, web, and book. But up to this point, it still feels more like a group of parts than a converging, transmediated storyworld. For example, there are “cyber-bridges” that extend the story beyond the written word. You can go to YouTube to see examples of his cyber-bridges. Cyber-bridges are video segments that occur approximately every 20 pages in the book, or even re-organize into its own one hour movie. To support the viewing of cyber-bridges, Zuiker hosts a free online community, Level26.com. To encourage readers to buy the book, the cyber-bridges must be unlocked using a printed code found in the book. (Of course, from an archival standpoint, one wonders what happens when and if the website goes offline in a few years for the book’s future readers.) I tend to find that the cyber-bridges interrupt my reading rather than plunging me deeper in the story. Cyber-bridges operate too often like cut-scenes in a video game, but without the feeling that one has “leveled.” And there can be a jarring effect when the characters in your reader’s “eye” are fleshed out in the video segments. I make note of these issues to highlight that Level 26 is still in an experimental stage. Zuiker himself has written on the problems he has faced in making all the pieces of the Level 26 franchise work.

Of particular interest to me is the community forming at Level26.com (which has had a community as large as 100,000 members). This is a community that is built for fans, aided by fans, but was not originally founded by fans. In fact, “official fan sites” can frequently be problematic, especially if readers sense that the community is little more than a marketing gimmick for a movie, TV show, or book. One way Level 26 is addressing this concern is to encourage fan participation on topics beyond the Level 26 novels, and making the site a destination for fans of serial killer fiction in general. How successful that maneuver will be has yet to be determined, but there are dedicated community members already operating around the subjects of serial killers, crime detection, and CSI: fandom. There is no doubt that Zuiker has learned a thing or two about building “franchises” from his CSI: success, and that this project benefits from his position in the media industries. In addition, Level26.com hosts fan contests, has a section for reader suggestions for future novels, and has active commentary sections related to the books.

Level 26 also takes advantage of handheld, touchscreen devices and in the process encourages active readers to click, touch, and play with the text and its digital components as the story unfolds on the screen. Using iPhone and iPad apps, Zuiker can eliminate the printed book’s hybrid status–straddling the analog-digital worlds–and produce a single, unified digital work. As Zuiker writes in February 2011: “”Years ago, when I started working on Level 26: Dark Origins, there wasn’t a device available to showcase my vision for what the Digi-novel could be. Now, with the release of the iPad, it’s time to unleash the Ultimate Digi-novel!” While the interactivity of Dark Prophecy as an app is still fairly rudimentary (and maybe not quite living up to the hype of being the “ultimate digi-novel”) nonetheless one can begin to see the promise of digi-novels as a mode of digital storytelling. Issues that have plagued early experiments in digital storytelling are still present in the app version of this novel. Beyond the interruptions of the cyber-bridges, pulling up electronic dossiers on characters or collecting evidence in the flow of a particular chapter can feel like tangents from the main storytelling rather than valuable hyperlinks. But even with these critiques, I fully appreciate how Zuiker is experimenting with digital storytelling and taking creative risks.

What might Level 26 suggest for the future of scholarly publication? First, the use of cyber-bridges would not be interruptive in a scholarly argument the way it is in a fictional narrative. I can see the potential of having cyber-bridges in a film or media studies book that could embed videos right alongside the written argument. Second, I think Level 26 points towards existing scholarly work that are moving more towards a “tablet-based reading” protocol or towards the expanded role of “video” in our reading practices. Here I sense deep affinities to a project like Alex Juhasz’s recent MIT Press “book,” Learning from YouTube.” For me, certain disciplines seem primed to continue these trends and experiments in scholarly publication, especially scholars in film, television, and new media.

I would love to hear about other examples around experiments in publishing, along the lines of Concord Free Press and the Level 26 franchise.